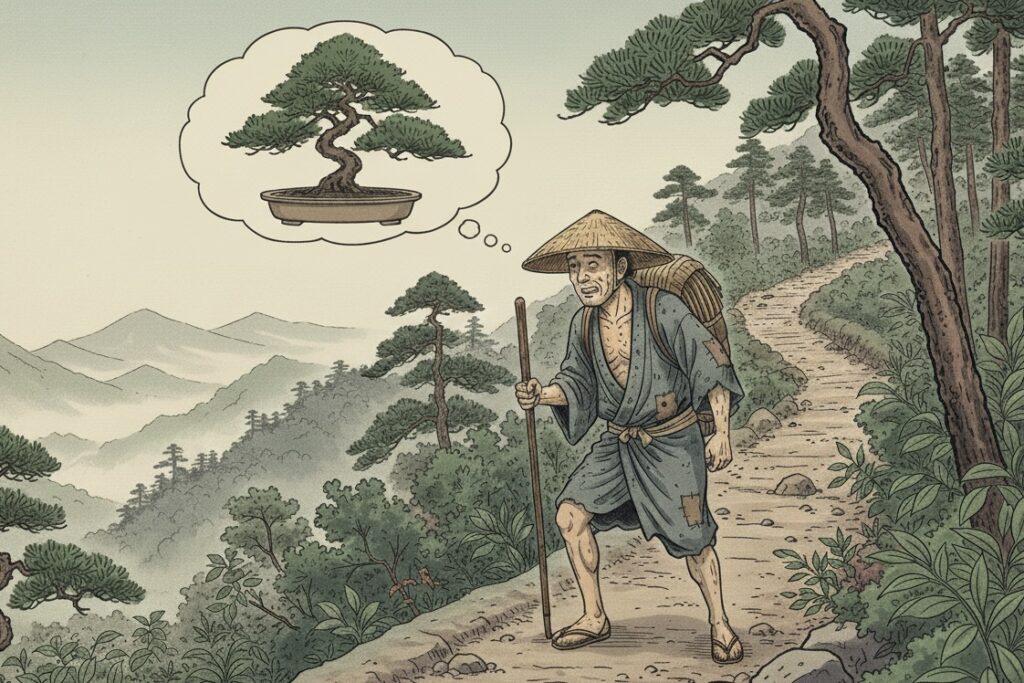

Why Bonsai Flourished in Takamatsu, Kagawa — Tracing the History (Part 2) —

I am writing from Takamatsu, widely known as a sacred center of bonsai.

When people speak of Takamatsu bonsai, they are usually referring to two neighboring areas: Kinashi and Kokubunji.

Among them, Kinashi in particular is renowned for its pine bonsai production. Ever since I was a child, I often heard people talk about the reputation of “Kinashi-brand” pine bonsai. The bonsai garden where I am currently learning and working is also located in Kinashi.

In this article, I would like to focus on the bonsai of Kinashi—and the background that gave rise to it.

Kinashi: A History That Began as “Barren Land”

Kinashi was once known by a very different name.

According to the Sanuki Province Map created during the Edo period, the area around present-day Kinashi was labeled “Kasai Kenashi.”

The word kenashi literally means “without hair,” and in this context referred to land so poor that rice and other crops could not grow.

The soil was thin and nutrient-poor, formed after debris flows, and rainfall was scarce. By any agricultural standard, it was an unforgiving environment.

Yet the people of Kinashi turned these apparent disadvantages into strengths.

The soil, though low in nutrients, was sandy and well-drained—conditions that turned out to be ideal for growing pine trees.

That said, pine bonsai is not produced throughout all of Kinashi.

Production became concentrated in specific areas: the Yamaguchi, Satō, and Kinashi districts. It was here that the core of Kinashi’s bonsai culture began to take shape.

Mandarin Orchards and Pine Fields: Same Soil, Different Uses

If we look at Kinashi from north to south, a clear contrast emerges.

The northern slopes are covered with mandarin orange orchards, while the flatter southern areas are dominated by pine fields.

In the northern Koretake district, a branded citrus known as Koretake mikan has long been cultivated.

Interestingly, many families in this area share the surname Kōno. According to local elders, their ancestors were former samurai who migrated from neighboring Ehime Prefecture. They are said to have brought mandarin saplings with them and introduced citrus cultivation to the area.

The land here is poor, sloped, exposed to intense sunlight and reflected heat, and touched by sea breezes.

At first glance, these conditions seem harsh—but for mandarins, stress is precisely what produces sweetness. In that sense, this land was ideal.

While written records are fragmentary, through conversations with local residents I have come to believe that this experience with citrus cultivation played a significant role in the later development of bonsai production.

After forming this hypothesis, I heard something particularly telling from the owner of the bonsai garden where I study.

He explained that even today, a number of bonsai producers in Kinashi are also involved in mandarin cultivation.

At that moment, everything clicked into place for me.

Mandarins and bonsai—two industries that seem unrelated at first glance—are in fact connected by a clear technical and historical continuity. I became convinced that this link was no coincidence.

Pruning, Seedlings, and the People Who Carried the Knowledge

At the heart of this story are people—and the techniques they passed on.

Figures such as Takahashi Shūsuke, a master of grafting; Kitayama Tasaku, who made his fortune producing conifer seedlings; and Kinashi Jinzaburō, who introduced apple saplings from the United States and expanded fruit tree nursery production—all played crucial roles.

The origins of bonsai cultivation in the region can be traced back to Takahashi Shūsuke.

Renowned for his exceptional grafting skills, Takahashi freely shared his techniques with others. Around the same time, Kitayama Tasaku succeeded in producing large quantities of pine and juniper seedlings, earning substantial profits.

One of Takahashi’s students, Kinashi Jinzaburō, went a step further by importing apple saplings from the United States and planting them in forests and fields.

As apple cultivation spread, demand for saplings surged, and fruit tree nursery production quickly expanded among neighboring farmers.

The skills developed through this nursery industry—

grafting, pruning, shaping trees, and managing growth in poor soil—

were later applied directly to bonsai cultivation.

From Wild Pines to Bonsai: The Origins of Kinashi Bonsai

Around 1887 (Meiji 20), individuals such as Yamane Benkichi of the Kinashi district and Tada Shinzō of the Satō district began collecting naturally growing pines from mountains like Goshikidai.

These yamadori (wild-collected) pines were then trained into bonsai.

At this point, all the elements came together:

the character of the land, pruning techniques from fruit cultivation, nursery production know-how, and high-quality wild pine material.

This convergence marked the true beginning of Kinashi’s pine bonsai tradition.

Kinashi Bonsai: Not an Accident, but an Inevitability

Pruning techniques from fruit trees, sandy soil, and low rainfall.

Each factor may seem coincidental on its own, but together they formed an inevitable outcome.

Kinashi bonsai did not emerge overnight.

It is the result of generations of people confronting an unproductive landscape and asking a simple, serious question: How can we survive here?

Their answers—expressed through accumulated skill and careful choice—continue to support the bonsai culture of Kinashi today.

(To be continued)