Why Bonsai Flourished in Takamatsu, Kagawa — Tracing the History (Part 1) —

The history of bonsai is ancient. Its origin is generally traced back to penjing, a Chinese art form that is said to have been introduced to Japan at least 1,200 years ago. However, the general history of bonsai in Japan is something anyone can easily look up online, so I will not go into it here.

What I want to explore instead is this question: Why did Takamatsu, in Kagawa Prefecture, develop into Japan’s leading production center for pine bonsai—especially black pine, often referred to as the “king of bonsai”?

Takamatsu bonsai is renowned not only for its volume but also for its exceptional quality. Anyone with even a moderate interest in bonsai will likely recognize names such as Kagawa, Takamatsu, Kinashi, and Kokubunji. So why did pine bonsai production flourish specifically in this region?

If we look back roughly 200 years, to the Bunka era of the Edo period (1804–1818), we begin to see the origins of Takamatsu bonsai. At that time, people collected naturally growing pine trees from nearby satoyama—such as Mt. Katsuga and Mt. Fukuro around Kokubunji—as well as from islands close to Takamatsu, including Megijima, Ogijima, Naoshima, and Shōdoshima. These trees were planted in pots and sold, forming the foundation of what would later become Takamatsu bonsai.

At this point, two questions arose for me. Why did people begin selling bonsai in the first place? And who, exactly, was buying them?

When I visited Takamatsu Bonsai no Sato in Kokubunji, I asked a staff member these very questions. The answer I received was surprisingly simple.

“There are several theories, but it’s said they were sold to people visiting Kotohira-gu Shrine.”

That explanation immediately made sense.

Kotohira-gu Shrine, located in Kotohira Town, Kagawa, has attracted worshippers from across Japan since the Edo period. Known especially as a guardian deity of the sea, it was visited by countless sailors praying for safe voyages.

During the Edo period, ordinary people were generally forbidden from traveling freely. Movement was strictly controlled for reasons of security and governance. However, religious pilgrimages—such as the Ise pilgrimage or the pilgrimage to Kotohira-gu—were granted special permission.

Acts of faith were considered free of personal indulgence, and for common people they provided rare moments of escape from everyday life. For the ruling authorities, these pilgrimages also functioned as a form of social “pressure release,” helping to maintain stability.

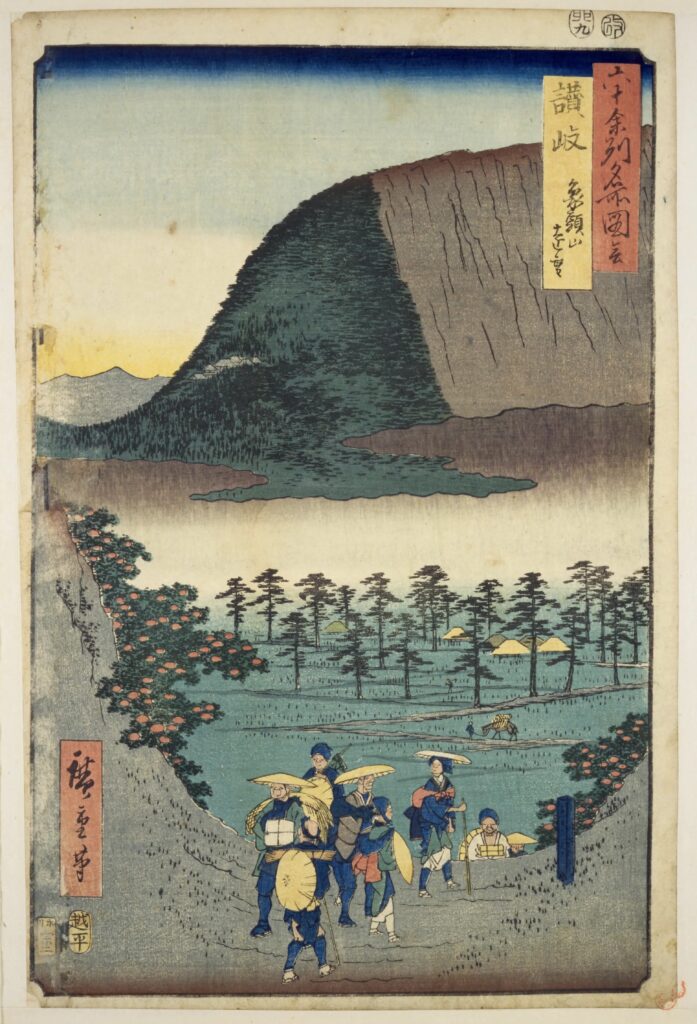

Famous Places in the Sixty-odd Provinces: Sanuki Province, Distant View of Mt. Zōzu (Kotohira-gu),

woodblock print, Edo period.

Source: National Diet Library Digital Collections, Japan.

Public domain.

Thus was born the journey to Kotohira-gu, often described as a once-in-a-lifetime trip.

Sold as souvenirs of this pilgrimage were bonsai made from wild-collected pine trees. In modern terms, this could be seen as an Edo-period version of an inbound souvenir business. Much like regional sweets sold at airports today, or limited-edition goods tied to travel experiences, these bonsai embodied both place and memory.

Pine trees, being evergreen, symbolize longevity and vitality. They are also part of the auspicious trio shō-chiku-bai—pine, bamboo, and plum. Compact, durable, and slow to wither, pine bonsai were perfectly designed as souvenirs. They were, quite literally, “experiences you could take home.”

The insight shown by the farmers of Kinashi and Kokubunji was remarkably sophisticated. Even from today’s perspective, their thinking feels strikingly modern.

I believe their ideas remain valid—and inspiring—more than 200 years later.

(To be continued)